William Jones, 2 Essex Villas (now Ravenhurst, 93 Pittville Lawn)

Between 1871 and 1891 William Jones lived with his family at No 2 Essex Villas (now “Ravenhurst”, 93 Pittville Lawn), the final house on Pittville Lawn before Albert Road. But the family only appeared once in the census for Pittville, in 1881. Their house, one of the large detached houses near the lake, was unoccupied at the time of the 1871 census, and by 1891 it was already occupied (and renamed “Ravenhurst”) by the next owners, the Smiths.

When asked by the 1881 census clerk to state his profession, William Jones offered the rather vague “Literary”, whereas in other censuses he had referred to private funds, dividends, and interest. William was underselling himself, as his varied literary productions (previously unresearched) extended back over forty years and would continue in one form or another for another decade or more. But William was not simply an author. Perhaps more noteworthy than his literary achievements was his role in the dramatic escape from France of King Louis Philippe and his queen Maria Amalia in the European Year of Revolution, 1848.

William was born around the year 1816 in the St Pancras area of London, the youngest of the five surviving children of John Jones, Gentleman, and his wife Sarah (née Watson). Both of his parents had been previously married. At some point (probably in the 1820s) the family moved from London to France, and it seems likely that William’s father took up a position in the British Consulate in Le Havre.1

There must have been frequent visits to England, though, as William associates some of the happiest moments of his youth with time spent in Warwickshire:

Towards the end of 1850, chance led me, after an absence of ten years, into Warwickshire… I determined to revisit the scenes familiar to my youth, and indulge in pleasant retrospections on the spot, where I had passed some of the happiest days it has been my lot to enjoy in this life of change. I accordingly took my place in the railway train from Coventry, (in my time an old coach and sedate team with an antiquated driver, more in character with the surround scenery, conducted the traveller to Kenilworth, by a route of remarkable beauty […]2

We encounter him as a writer in the pages of the respected literary magazine Bentley’s Miscellany, published by Richard Bentley, in 1840. Bentley had established the magazine under the editorship of Charles Dickens in 1836, but the two men had fallen out and Bentley found a new editor in William Harrison Ainsworth in 1839. Jones was in good company, as over the years the magazine published work by such people as Wilkie Collins, Thomas Love Peacock, and Edgar Allan Poe, as well as by its editors Dickens and then Ainsworth. The magazine also offered space for many other new talents.The identity of William Jones as a minor literary figure has puzzled commentators and critics. In her review of “Verse in Bentley’s Miscellany vols. 1 – 36” Eileen M. Curran notes that:

So far 158 contributors of verse have been identified [in the Miscellany], almost half of them represented by a single poem. Only 29 contributed more than five, with the unexceptionally named William Jones being responsible for an exceptional 83 poems.3

It must have seemed impossible to discover any more about the “unexceptionally named William Jones”. Many of Jones’s poems took antiquarian or medieval themes, in keeping with early Victorian preferences. They are often sentimental, but their taut structure and precise phraseology often place them above much of the rigmarole of the day. The first of Jones’s poems to be published in Bentley’s Miscellany was one of his most praised: “The Monks of Old”, which consists of six verses in this style:

Many have told of the monks of old,

What a saintly race they were;

But 'tis more true that a merrier crew

Could scarce be found elsewhere;

For they sung and laugh'd,

And the rich wine quaff’d,

And lived on the daintiest cheer. 4

Jones was the most prolific contributor of poetry to Bentley’s Miscellany throughout the 1840s. With some intervals he continued to contribute into the 1860s. Many of these pieces were published in his collection Horæ monasticæ, poems, songs, and ballads (London and Warwick: 1853). The collection was dedicated to his brother, the Reverend John Jones.

Some of these poems were written while Jones was employed in the British diplomatic service. In 1845 he was appointed British Vice-Consul at Le Havre,5 working under the Consul George William Featherstonhaugh (pronounced “Fanshawe”: 1780–1866), a Briton who had previously built up a considerable reputation conducting geological surveys for the American Government in the eastern United States. Featherstonhaugh and Jones are remembered for their role of the escape of King Louis Philippe and his queen Maria Amalie from Paris in late February and early March 1848, as the threat of revolution engulfed Europe. The King rapidly abdicated in favour of his nine-year-old grandson Philippe and set off for England and (comparative) safety. En route they waited in Monsieur de Perthuis’s house at Honfleur for a ship to transport them. The New Monthly Magazine (in which Jones also published) took up the story:

On Thursday, the 2nd of March, the hosts of M. de Perthuis’ house experienced a new alarm: at break of day, a stranger, bearing a message, asked to be allowed to speak to the king. This stranger was Mr. Jones, English vice-consul at Havre. The message was from Mr. Featherstonhaugh, consul. He announced that the steam-packet the Express was at his disposal, and that Mr. Jones was deputed to concert with his Majesty upon the means of getting on board… The fugitives resolved upon travelling from Honfleur to Havre by the night boat. The queen was to be Madame Lebrun, travelling with an English passport; the king had been Mr. William Smith. Mr. William Smith, wearing spectacles, and wrapped up in a capacious cloak, found Mr. Jones waiting for him on the quay ... On disembarking at the quay of Havre, in the midst of a crowd of promenaders, travellers, and hotel touters, the first person they met with was the English consul […]6

Jones’s conversation with the French king is recorded:

Then taking my hand the King said — "You have been kind to us, may I ask your name?" I told His Majesty that I was Vice-Consul at Havre, under Mr. Consul Featherstonhaugh, whom he knew. I told him that Her Majesty’s Government had great concerns for his safety, and had sent steamers to aid him in his flight, at which the Monarch was much affected, and said — "With such an excellent Queen and Government, an Englishman may indeed be envied!"7

Bentley’s Miscellany published an account of the escape (“Eight days of a royal exile”), adding a note on the reference to Jones:

Mr. William Jones, British Vice-consul at Havre, an excellent young man, of superior intelligence, and with a spirit equal to the noble experience which he undertook, also assisted worthily.8

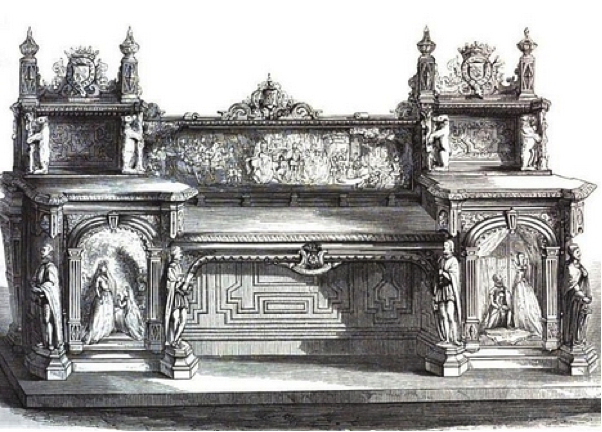

The Kenilworth buffet9

In 1850 Jones’s consular service came to an end, and he returned to England. The following year saw his first book publication, a twenty-two-page illustrated pamphlet with an antiquarian bent, describing “the Kenilworth buffet”, a large, decorated sideboard based on the theme of Sir Walter Scott’s Kenilworth, prepared by a Warwick company for the Great Exhibition of 1851.10 The buffet” is now on display in Warwick Castle.

Jones married twice. His first marriage, to Elizabeth Carey McCrea, took place in her native Guernsey, though he lived at Brent House in Brentford (where Nell Gwynn was said to have lived and where King Charles II apparently rode a horse up the stairs). But the marriage was sadly short-lived and without issue. Elizabeth died in London in 1857.11 But during the time of his first marriage William had taken a decisive step and in December 1855 was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London.12 In the future it was principally as a writer on antiquarian and especially scientific curiosities, rather than as a poet, that he was best known.

At the same time as his election to the Society of Antiquaries William was preparing his “descriptive notices” written to accompany the illustrations in Philip H. Delamotte and Joseph Cundall’s Photographic tour among the abbeys of Yorkshire.13 It is at this point that his interests seem to shift from historical description to informative and educational texts. He identified a new market for manuals and compendia, and found it easy to write such texts, typically drawing together excerpts taken from classical and modern writers and presenting them in what critics sometimes regarded as an informal and gossipy tone.

The first of this new breed of production was his How to make home happy: or, Hints and cautions for all, published in 1857, and revised in 1862 as Household hints; or How to make home happy.14 The Leader and Saturday Analyst admired Jones’s style:

Mr. Jones is a man of versatile capacity. He travels with the photographers of Yorkshire; he writes monastic Horae; and he mixes this wonderful olla podrida of cookery, gardening, carpet dusting and platitude – a useful, but an eccentric volume… Part of his didacticism is to be laughed at, part is to be obeyed.15

This was succeeded in 1858 by another domestic compendium, this time entitled Health for the Million.16 Unusually, his name did not appear on the title-page, though it was published by the author of “How to make home happy” (his previous book), is written in his characteristic excerpting style, and was issued by one of his former publishers D. Bogue (by then W. Kent and Co.). On this occasion he dedicated the book to his brother Alfred, a surgeon:

To Alfred Jones, Esq., M.R.C.S. Engl., L.S.A. this book is affectionately inscribed by the author

At the end of 1859 he remarried, this time to a Cornishwoman, Caroline Davey. Although he was living back in his old haunts of Camden in London, the marriage took place at the British Embassy, in Paris:

On Monday, 27th Dec. last, at the British Embassy, Paris, by the Rev. J. Swale, William Jones, Esq., F.S.A., &c., of London, formerly British Vice Consul at Havre, to Caroline, the only surviving daughter of the late Thomas Davey, Esq., of Tuckingmill, Cornwall.17

The couple lived in London into the early 1860s, and this was where their first three children were born: Herbert Charles Walter (1860), Marie Amelia Emma (c1862), and Wilfred Aubrey (1863). At this point William Jones did not publish anything new, but revised his Household Hints (1862). The family moved closer to where Caroline came from, to Broadgate Villa, Pilton near Barnstaple in North Devon, and two more children were born: Mildred Avice (1864) and Cuthbert William (1867). But William had been at work on more poetry (a flurry appears in Bentley’s between 1866 and 1870), and he must have been busy with his next book, a scientific compendium called The treasures of the earth: or, mines, minerals, and metals. This time his publisher was Frederick Warne (1867 but title-page 1868; ed. 2, 1869). Having dealt with the contents of the earth, Jones next moved his perspective to the contents of the sea, and in 1870 Warne published his Broad, broad ocean and some of its inhabitants, dedicated to his young son Cuthbert. This was followed, like The Treasures of the Earth, with a second edition the following year, perhaps his first production from Cheltenham.

The family, which now consisted of William and Caroline and their five children, moved from north Devon to Cheltenham soon after April 1871. Herbert and Wilfred entered Cheltenham College as day-boys in October 1872; Cuthbert had to wait until January 1882. William had shifted his focus of interest yet again, this time firmly to antiquarian and folkloristic topics. His next voluminous texts were published by Chatto and Windus, and were entitled Finger-ring lore: Historical, legendary, anecdotal (1877 [i.e. 1876], Credulities past and present (1880), and Crowns & coronations: A history of regalia (1883). Each text ran to more than one edition. In 1880 he also wrote on gemmology for Richard Bentley, in the History and mystery of precious stones (1880). William was by now a member of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.18

The family, which now consisted of William and Caroline and their five children, moved from north Devon to Cheltenham soon after April 1871. Herbert and Wilfred entered Cheltenham College as day-boys in October 1872; Cuthbert had to wait until January 1882. William had shifted his focus of interest yet again, this time firmly to antiquarian and folkloristic topics. His next voluminous texts were published by Chatto and Windus, and were entitled Finger-ring lore: Historical, legendary, anecdotal (1877 [i.e. 1876], Credulities past and present (1880), and Crowns & coronations: A history of regalia (1883). Each text ran to more than one edition. In 1880 he also wrote on gemmology for Richard Bentley, in the History and mystery of precious stones (1880). William was by now a member of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.18

By the time of the 1881 census the family had three live-in domestic servants.19 At this stage, William may well have felt confident describing himself to the census clerk as “literary”, rather than a “fund-holder”, as he presented himself at other times. His last new text was published when he was well into his seventies: Glimpses of animal life. A naturalist’s observations on the habits and intelligence of animals (London, E. Stock: 1889).

Soon after this, he moved with his family round the corner and up Albert Road, to Marston Lodge, on the way towards Prestbury. The family was there for the 1891 census. The 1890s saw children married, work on new editions of his own works, and rheumatism. In a series of notices run in the Gloucester Journal in December 1890 “William Jones, Esq., F.S.A., Pittville, Cheltenham” informed his readership that he had “found great relief from Rheumatic pains by the use of the ‘Magneticon’ Appliances.”20 The family still lived at Marston Lodge when his son Wilfred was married in 1896, but in due course William and Caroline migrated back to Devon. It was at their home, “Ermenhurst”, East Cliff, Dawlish, that William Jones died, on 11 November 1904, at the age of 88. He had helped an old king escape, had just seen out the old queen, whom he had served as Vice Consul fifty-nine years earlier, had seen his five children make a start in the world, and had launched an armful of poems and a handful of books on the world. He must have pleased in general with the way things had gone.

John Simpson

1 See http://gw.geneanet.org/garric?lang=fr&p=sarah&n=jones.

2 William Jones An account of the Kenilworth buffet, with elaborately carved relievos, illustrative of Kenilworth Castle in the Elizabethan period, designed and executed by Messrs Cookes and sons, of Warwick for the Grand Exposition of Industry of all Nations (London - J. Masters; Cundall and Addey; Warwick: H. T. Cooke: 1851) p. 4.

3 Eileen M. Curran “Verse in “Bentley’s Miscellany vols. 1-36”, in Victorian Periodicals Review vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer, 1999) p. 118. See Curran for an index to Jones’s poems in these volumes. The standard cumulative index of Victorian poetry incorrectly describes Jones as “of Warwickshire”.

4 Cited from The Bentley Ballads (London, Richard Bentley: 1861), containing “the choice ballads, songs and poems contributed to “Bentley’s Miscellany”, pp. 61-2.

5 Foreign Office List (1878), p. 128.

6 New Monthly Magazine (1855), vol. 103 p. 404.

7 British Documents on Foreign Affairs - reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: France, 1847-1878 (1989), p. 17.

8 Bentley’s Miscellany (1850), vol. 28 p. 324.

9 Official descriptive and illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition (1851), vol. 3 sect. 3 class 30 facing p. 827.

10 William Jones An account of the Kenilworth buffet, with elaborately carved relievos, illustrative of Kenilworth Castle in the Elizabethan period, designed and executed by Messrs Cookes and sons, of Warwick for the Grand Exposition of Industry of all Nations (London & Warwick: 1851).

11 Gentleman’s Magazine New Series (1854), vol. 42 p. 294; Gentleman's Magazine New Series (1857), vol. 47, p. 253.

12 Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries (1856), vol. 3 p. 230.

13 Philip H. Delamotte and Joseph Cundall A photographic tour among the abbeys of Yorkshire… With descriptive notices by John Richard Walbran [F.S.A.] and William Jones [F.S.A.] (London, Bell and Daldy: 1856).

14 William Jones F.S.A. How to make home happy: or, Hints and cautions for all (London: 1857); William Jones Household hints; or How to make home happy (London: 1862).

15 Health for the Million, by the author of “How to make home happy”, “The accidents of life”, etc. (London: 1858). Library catalogues (including that of the British Library and the Bodleian Library in Oxford have as yet failed to identify Jones as the author of this text. The Bodleian Library has correctly identified his other book publications, but the British Library does not yet associate him with his Account of the Kenilworth Buffet (1851), nor with his Horae Monasticae (1853). On the title-page of Health for the Million Jones is also said to be the author of "The accidents of life"; on the title-page of Horae Monasticae (1853) he is credited as the author of "Lays and Ballads of French History". Neither of these titles is listed in the principal bibliographies, so their status remains uncertain.

16 Leader and Saturday Analyst (1857), 14 March p. 257.

17 Royal Cornwall Gazette (1859), 7 January.

18 Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society (1879), vol. 4 p. 363.

19 Their son Wilfred Aubrey was not at home, apparently, on census night.

20 E.g.: Gloucester Journal 13, 20 December.